Artists for a Lifetime

I am still very much in love with what I do and am fascinated by the alchemy of what drives people to a lifetime of making art. Over the past 15 years, I’ve set out to capture some of those truths through photographs of accomplished artists with many years inscribed in their being – visual artists, writers, performance artists, musicians – whose unflinching commitment to their work bespeaks the bewitching pull of the creative life.

-

DONNA DENNIS Sculptor, Painter, Printmaker, Recipient Pollock-Krasner Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation...

-

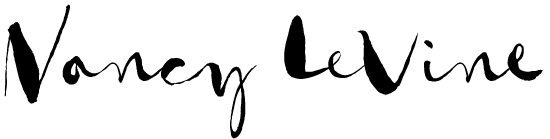

DOROTHEA ROCKBURNE Abstract Painter, Collected MoMA, DIA...

-

JANE COMFORT Choreographer, Dancer, Director, Guggenheim Fellowship, Recipient National Endowment for the Arts...

-

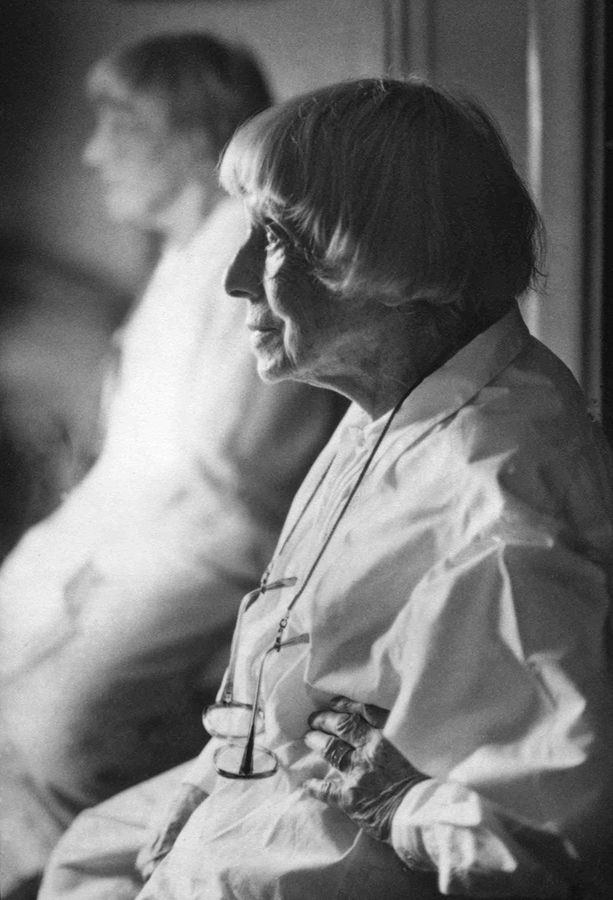

LOUIS STETTNER Photographer, Life Magazine, Street Photographer of New York and Paris...

-

MICHELE OKA DONER Artist, Collected Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Louvre...

-

ROCHELLE FEINSTEIN Visual Artist, Collected Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim Fellowship...

-

![William Ivey Long Costume Designer Six Time Tony Award Winner]()

WILLIAM IVEY LONG Costume Designer, Six Tony Awards...

-

![Martin Greenfield Master Tailor, Auschwitz Survivor, Tailor to Presidents Eisenhower, Lyndon B. Johnson, Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford, Barack Obama...]()

MARTIN GREENFIELD Master Tailor, Auschwitz Survivor, Tailor to Presidents Eisenhower, Lyndon B. Johnson, Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford, Barack Obama...

-

![Photographer Mary Ellen Mark]()

MARY ELLEN MARK Documentary Photographer, Published Life, Rolling Stone, The New Yorker, Member Magnum, Documentary Film 'Streetwise'...

-

![Arthur Giron Playwright]()

ARTHUR GIRON Playwright, Winner of the Galileo Prize for Playwriting, Los Angeles Critics Award for Outstanding Achievement in Theatre, Broadway...

-

![Photographer Ise Bing, Photojournalist, Published in Le Monde, Vogue, Exhibition Museum of Modern Art, Louvre...]()

ILSE BING, Photographer, German, Notable Career in Paris, Photojournalist, Published in Le Monde, Vogue, Exhibition Museum of Modern Art, Louvre...

-

![Dr. Ruth Gruber Photographer, Journalist, Writer, Humanitarian, U.S. Government Official, Documented Holocaust survivors on the ship Exodus...]()

DR. RUTH GRUBER Photographer, Journalist, Writer, Humanitarian, U.S. Government Official, Documented Holocaust survivors on the ship Exodus...

-

![Rosaire Appel Book Artist, Graphic Novellas, Abstract Comics, Asemic Writing...]()

ROSAIRE APPEL Book Artist, Graphic Novellas, Abstract Comics, Asemic Writing...

-

![Raquel Rabinovich Artist]()

RAQUEL RABINOVICH Painter, Sculptor, Hudson River Installations, Collected Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art...

-

![Billie Allen Actress]()

BILLIE ALLEN Actress, Theater Director, Dancer, Entertainer, Broadway, Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio...

-

![Arthur Leipzig Photographer]()

ARTHUR LEIPZIG Photographer Photo League, Included in Exhibition 'The Family of Man', Look Magazine...

-

![Deborah Eisenberg Short-Story Writer, Actor, Recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and a PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction]()

DEBORAH EISENBERG Short-Story Writer, Actor, Recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and a PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction...

-

![Photographer and Biologist Roman Vishniac, 'A Vanished World'...]()

ROMAN VISHNIAC Photographer, Russian Immigrant, Documented Jewish Life in Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust, Book "A Vanished World', Included in 'The Family of Man', Biologist, Research Associate at Albert Einstein College of Medicine...

-

![Millicent Young Sculptor]()

MILLICENT YOUNG Sculptures and Installations, Living in the Time of Extinction, Sculpture Magazine Cover, Awards with curators from National Gallery/Smithsonian, Hirshhorn, Dia,Guggenheim, Whitney Museum...

-

![Rebecca Lepkoff Photographer]()

REBECCA LEPKOFF Photographer, Photo League, Street Photographer Lower East Side, Collected National Museum of Art, Howard Greenberg Gallery...

-

![Richard Meier Architect]()

RICHARD MEIER Architect, Pritzker Prize, Modernist, Designed the Getty Center, Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art...

-

![Connie Caruthers Jazz Singer]()

CONNIE CARUTHERS Jazz Singer, Composer, Pianist, Founded New Artists Records with Max Roach...

-

![Maggie Newman Tai Chi Master]()

MAGGIE NEWMAN Tai Chi Master, Senior Student of Great Master Professor Cheng Man Ching...

-

![Amy Trompeter Puppeteer]()

AMY TROMPETER Puppeteer, Trumpeter, World Theater Historian, Founder Redwing Blackbird Theater, Roots in Bread and Puppet Theater in 1960's...

-

![Sheila Jordan Jazz singer]()

SHELIA JORDAN Jazz Singer, Songwriter, NEA Jazz Master, Bebop and Free Jazz, Professor, Performed with Ben Kuhn, George Russell, Roswell Rudd...

-

![Suzanne Thorpe Musician Composer]()

SUZANNE THORPE Musician, Site Specific Compositions, Mellon Teaching Fellow/Lecturer in Music at Columbia University, Performances Manitoga, River to River Festival...